Seeing Is An Action Word

Commissioned by Gibney’s Imagining, A Gibney Journal 2022.

Welcome.

I hope this finds you well.

My name is Jesse Obremski; my pronouns are he/him. I am a non-disabled, cis-gendered, Japanese-American artist, performer, choreographer, educator, director, and more. I have black eyes, short black hair, I am 6 feet tall, and I am usually wearing something from Uniqlo. I currently live in Harlem, New York, stolen Munsee Lenape and Wappinger land, where I primarily wrote this offering for Imagining: A Gibney Journal’s March 2022 issue. (I am recording this audio version of my written Imagining: A Gibney Journal offering in studio 4 at 890 Gibney.)

I often remind myself, and encourage others, to see the larger picture. Something that is easier said than done. It is a task that tends to be more difficult but vital because it requires community and conversation. It requires others and not just oneself. This offering in Imagining is part of my effort toward this ethos and culture. I share large questions often and by no means have any finite answers. However, I continually process and unpack them daily. In the ethos of a more global viewpoint, I want to take this time to remind us of the incredible work of first responders and health care workers, especially through these trying years of Covid-19. Stay safe, and thank you.

I recently learned through research that the owl, in fact, does not have the largest field of vision. The bird with the largest field of vision is the American woodcock. I find this incredibly ironic because the United States has much to work on in terms of seeing all viewpoints of our world, in seeing all of humanity. In acknowledgment of how intention and impact may be different, this essay is in no way intended to isolate, prohibit, cover, and/or silo any experience but rather to highlight a viewpoint into cultural experiences and thoughts from an Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) perspective–a perspective that may support us in acknowledging the larger picture, the largest field of vision, and a larger spectrum of humanity. As we move forward in this essay together, I want to share a friendly reminder to accept breaks, take conscious breaths, and do what you need, away from the screen or device to take care today, tomorrow, and always.

Since joining Gibney Company, I have been diving into my Gibney Company Moving Toward Justice Fellowship. These fellowships are where each Artistic Associate explores and creates programming on a need we recognize within the field. OUR PATHS, my fellowship, which launched in the Spring of 2020, is where we cultivate, curate, and celebrate a culture of accountability, reason, and clear purpose towards greater communal empathy. In a culture of “who, what, where, when, and sometimes why,” I encourage us to challenge this norm and begin with WHY.

After reading Simon Sinek’s book Start With Why at the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, I found OUR PATHS to be a springboard towards this culture of celebrating “why.” More can be learned about OUR PATHS at www.ourpaths.life. I invite us to continue forward with this written offering of personal viewpoints on how AAPI culture is viewed with a lens of curiosity, WHY, and empathy.

As a mixed artist, I continually have a complex time being able to settle in with this ever-developing “label” of myself. I am frequently asked by society and culture: “How do you identify?” or “Where are you from?” These questions suggest space for one to define what their identity is, but they force one to clarify and label oneself for that day, time period, or moment.

I recently had a conversation with a colleague, and we discussed how our culture often introduces one another by name and credentials. At an audition or job application, it is often the name and credentials. It is the who, what, where, and when, rather than the why. This relates to the culture of labeling. Everything is about seeing, perspective, context, balance, and I do recognize that labeling can also be a sign of immense pride.

I personally have immense pride as a New Yorker. My experiences in New York City are what have developed my passions, my drive, and the reasons why I do what I do. Though I am thankful to have been encouraged and supported by my family in sharing my identity as I grew up in New York, in retrospect, I became extremely naive about my personal ethnicity. I grew up without this other sense of pride: my heritage. With years of independent discovery on this and cultural progression, I ask, Why are things different for me now? This is our first “why” question and I invite you to keep note of them throughout this essay. Here is question number two: Why was I naive about my inner strength and not acknowledging my heritage?

Now, in 2022, we find ourselves immersed in a constant challenge to change the global culture, to shift and evolve. It is because our culture has to change. This is innately human as noted by Measure of America (www.measureofamerica.org) that human development is “the process of enlarging people’s freedoms and opportunities and improving their well-being.” Even though they define “human development” as such, is it really true? Whose “well-being” are they referencing?

Gilbert T. Small II, currently Gibney Company Director, has had an extensive performance background with Ballet BC and an international perspective. Gilbert shared with the company, at the beginning of the 2021-2022 season in September 2021, that our “culture is shifting and it is going to get worse before it gets better.” This is part of the cultural revealing we are immersed in, and I believe there are multiple examples of this unfolding within our society.

In the midst of a global pandemic, assault on Black and Brown lives and marginalized communities yet again surged. George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Tamir Rice, Trayvon Martin, Sandra Bland, Eric Garner, Walter Scott. Rest in power. These are only a few of the individuals who have had their lives stripped from them. I specifically say marginalized communities because, in relation to the hate crimes on Black and Brown communities, there have been countless more tragedies and assaults on individuals across the spectrum of humanity.

Almost a year ago, on March 16, 2021, a shooting spree occurred across Atlanta, Georgia–in particular, at Young’s Asian Massage and Gold Spa. Eight people were murdered, six of whom were AAPI women (Delaina Ashley Yaun, Paul Andre Michels, Xiaojie Tan, Daoyou Feng, Hyun Jung Grant, Suncha Kim, Soon Chung Park, Yong Ae Yue). This sparked more engagement across our world with #stopAAPIhate.

All of these vicious acts point to the worsening condition of our society. Gilbert believes—and, in my heart, I share this belief—that we can get better. Communities are gathering together, affirming cultural unity and solidarity. Within the AAPI community, I have found a deepened sense of cultural purpose through festivals, activism, and conversations to highlight the full AAPI diaspora. Though there is this incredible momentum, here is “why” question number three: Why has representation barely been apparent within our dance culture? This question often comes up, though only the surface gets addressed. Does it really take the loss of lives to make movements for justice happen?

Hong Kong-born dancer, arts advocate, and activist Phil Chan, based in New York, is diving deeper. With Georgina Pazcogin—an incredible AAPI artist and soloist with New York City Ballet—Chan founded Final Bow for Yellowface in 2017. Final Bow addresses the usage of “yellowface” and Asian stereotypes within primarily ballet works and companies. Recently, Final Bow has expanded its support of AAPI artists.

“Looking around at other communities who have organized centers like Dance Theatre of Harlem and Ballet Hispanico, the Asian ballet community doesn’t really have that,” Chan told me. “We haven’t consciously made that space. Maybe it’s because we have been conditioned to be more passive, or perhaps because at least we are in the room if not fully at the table. So maybe it’s better just to keep your head down and work harder.”

“Conditioned to be more passive.” That’s oppression. Within oppressive US culture, based on colonialism and white supremacy, AAPI culture goes unseen and AAPI voices go unheard. It is unpromising that cries from AAPI individuals continually go unrecognized. This is a reality for many.

Though I recognize that I have this space to share through Imagining, I have been humbled with opportunities and have incredible support, this is still a reality for me as well. I have felt the cultural pressure to silence my voice while others speak over me. I have felt seen through the lens of stereotyping: that AAPI people work hard and do not speak. I have felt spaces of underappreciation and discrimination. This is real and is heavy, but I have been “conditioned to be more passive” to keep my “head down and work harder.” I have been affected by oppression.

A 2019 article by Zara Abrams for the American Psychological Association shared evidence from Ascend, Pan-Asian Leaders that AAPI individuals–representing 6% of the United States, the fastest-growing population within the US–“are frequently denied leadership opportunities and are overlooked in research, clinical outreach and advocacy efforts.”

“AAPI’s presence has been historically and conveniently washed out in this homogenized society, and often only Black and white conversations come up when we talk about race” shares Jie-Hung Connie Shiau, a Gibney Company Artistic Associate and choreographer. Jie-Hung–from Tainan, Taiwan–has a lived experience of a Third-Eye view of the United States. The washing out of AAPI culture limits the potential for a global community. It isolates AAPI individuals and has contributed to the rise of anti-AAPI violence in the United States.

Gibney Company is in our second creative process with Inaugural Choreographic Associate Rena Butler, exploring Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave” from his book, The Republic. The theory is in The Republic, volume VII, with translation by Thomas Sheehan.

It opens with a sentence from Plato’s teacher, Socrates: “Next, said I, compare our nature in respect of education and its lack to such an experience as this.”

So, let’s explore this. This reference to education is a reason WHY I, and potentially many other AAPI individuals, grew up being naive. Artist or not. I was conditioned by society to have my inner voice be more passive through my education or lack thereof. To not recognize, be proud, or be courageous about my Japanese-American heritage. I was oppressed into invisibility.

American pop culture explodes with superheroes, and invisibility is often seen as an incredible power. But not this invisibility. This is disempowerment. I believe an amazing superpower, and therefore responsibility, is actually seeing, like the American woodcock, a wide field of vision. Seeing those who are invisible and even those made invisible.

It was my conscious intent to offer this essay for Imagining‘s March issue, two months before AAPI Heritage Month. I want to encourage us to examine if AAPI artists and others are recognized and supported in our society and its institutions only during May. Will there be increased visibility?

And that brings us to our next, and fourth, “why” question? Why give cultures and cultural movements just a single month of recognition? A necessary start, but this is silo-ing.

As Jie-Hung/Connie has said, “AAPI presence is often still under-represented considering how massive and diverse Asia is.”

There is so much to celebrate within the AAPI diaspora. In our effort to see a larger picture, let’s recognize that this is the same for Africa. The continent of Africa is incredibly diverse—historically, politically, culturally, artistically—and its great diversity is under-recognized in the white Western mind.

There are twelve months to a year. I invite us to find ways to celebrate every culture year-round because marginalized cultures are not invisible for the other eleven months.

Each time I have worked on this essay, I have asked myself, “What is different? What has changed from just one month ago?”

For one thing, I noticed more AAPI content on media platforms such as Netflix. At first, I found this exciting, but then I took a closer look through a larger lens. Maybe it wasn’t so much that more AAPI material was being presented. Maybe it was just the algorithm feeding back more of the kind of content I had supported in the past. It’s hard to tell what’s real.

One thing I know to be true from the people in my life is that AAPI individuals are hurting. This is real, and I see it. This brings us to our fifth question: Why does our culture need these constant reminders?

Though things may be tough, I feel optimism in my bones. There are those reminding our world of AAPI presence and doing the work. For example, Jessica Chen–an artist, advocate, and Founder/Director of JChen Project–has created festivals and movements to reveal more of the AAPI experience. Her festival, We Belong Here: AAPI Dance Festival, has the organizational support of Arts on Site, which has committed to producing the festival for the next three years. This is one example of sustained support of AAPI culture, experiences, and voices.

Where do you see sustained support of AAPI individuals in your life? How can we shine a light on AAPI artists who have felt invisible for so many years?

I encourage you to take a deep breath and be empathetic to yourself. I have posed large questions that take time to process. I hope you can find ways to bring yourself to my personal discovery and offering. I encourage you to take the “why” questions throughout this article and investigate for yourself, how do I approach these questions? How do I connect with them?

Why are things different for me now?

Why was I naive about my inner strength and not acknowledging my heritage?

Why has representation barely been apparent within our dance culture?

Why give cultures and cultural movements just a single month of recognition?

Why does our culture need these constant reminders?

Thank you for your time in joining me to dive into these questions. I invite you to find ways to celebrate marginalized communities throughout every month of every year and uplift these voices.

I want to name and support the community of individuals who have supported this offering: Eva Yaa Asantewaa and Monica Nyenkan, the editorial team for Imagining: A Gibney Journal; Richard Sayama; Gilbert T Small II; Jessica Chen; Phil Chan; Jie-Hung Connie Shiau; Michael Greenberg; Rena Butler; Gibney’s Community Action Department, and all of you who have taken the time to absorb these perspectives.

I also look forward to hearing your thoughts as we continue our global conversation and development. Connect with me at jesse.obremski@gmail.com and www.jesseobremski.com.

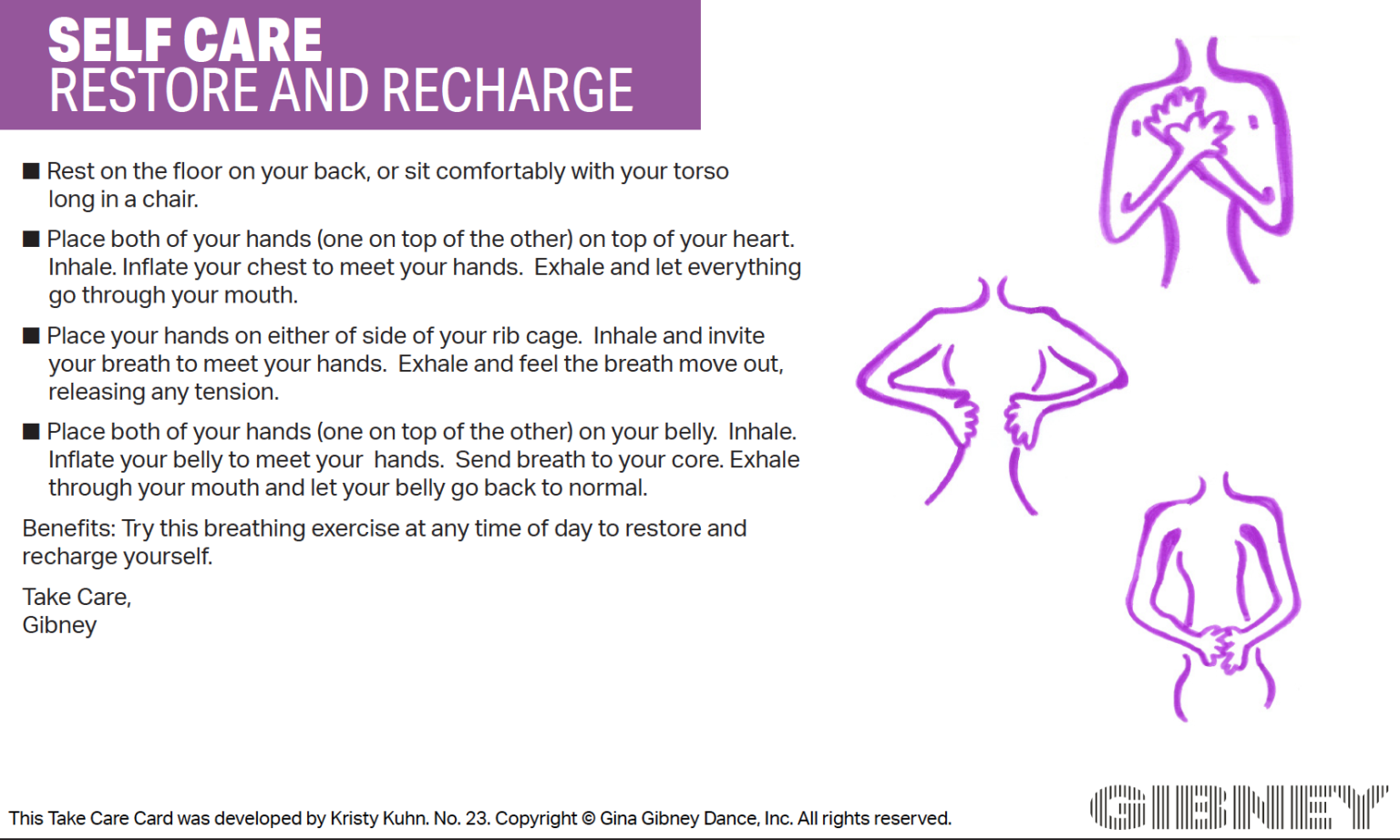

And, finally, I’d like to offer this Take Care Card, created by Gibney’s Community Action team, developed by Kristy Kuhn, as a way to support yourself moving forward:

Self Care:

Restore and Recharge

Rest on the floor on your back, or sit comfortably with your torso long in a chair.

Place both of your hands (one on top of the other) on top of your heart. Inhale. Inflate your chest to meet your hands. Exhale and let everything go through your mouth.

Place your hands on either side of your rib cage. Inhale and invite your breath to meet your hands. Exhale and feel the breath move out, releasing any tension.

Place both of your hands (one on top of the other) on your belly. Inhale. Inflate your belly to meet your hands. Send breath to your core. Exhale through your mouth and let your belly go back to normal.

Benefits: Try this breathing exercise at any time of day to restore and recharge yourself.

Take Care,

Gibney

A horizontal image with a white background and a black thin-lined box contains the Restore and Recharge

invitations to the left. Inside this black box are three drawings of torsos to the right. One illustration features

hands on top of the heart, the other shows hands on either side of the rib cage, and the last portrays hands on the belly. The Take Care Card title is on the top left in a purple box. On the bottom right is the Gibney logo.

In mid-February, while this essay and Imagining Journal were in the editing process, Christina Yuna Lee was murdered in her Chinatown apartment. She was stabbed more than 40 times. This occurred within a month of numerous anti-AAPI hate crimes, primarily victimizing female-identifying individuals, especially in New York City subways and public spaces (Michelle Go, Atsuko Obando, Potri Ranka Manis, to name just a few).

According to NBC News, anti-AAPI hate crimes have increased by 361% since 2020. Jo-Ann Yoo, Executive Director of the Asian-American Federation, shares that this data is highly underreported. These hate crimes must stop.

I share my condolences, respect, and support to all who are hurting now and I invite everyone to take conscious breaths, be aware, and take care.

- Jesse Obremski